Jesse Wright on representing his Jamaican roots through his art

Bronwyn Hunter-Shortly on July 27, 2022

As we approach the launch of Peggy, we’re thrilled to give everyone a sneak peek into some of the Pegcasts that will be live on the app.

Bronwyn Hunter-Shortly, VP of Art at Peggy, chatted with Jesse Wright and learned about his artistic practice, how his Jamaican heritage influences his work, and the way that he thinks about art making. Let’s get into the conversation!

Jesse Wright is represented by LatchKey gallery and lives and works in New Jersey.

Jesse Wright. Credit Jesse Wright via SUNDAYREBEL.

Jesse Wright. Credit Jesse Wright via SUNDAYREBEL.

Bronwyn Hunter-Shortly: Hi, Jesse, where are we reaching you today?

Jesse Wright: I am in New Jersey, about 20 minutes from George Washington Bridge.

BHS: You are an artist, but you're also a teacher. Tell me a little bit more about that.

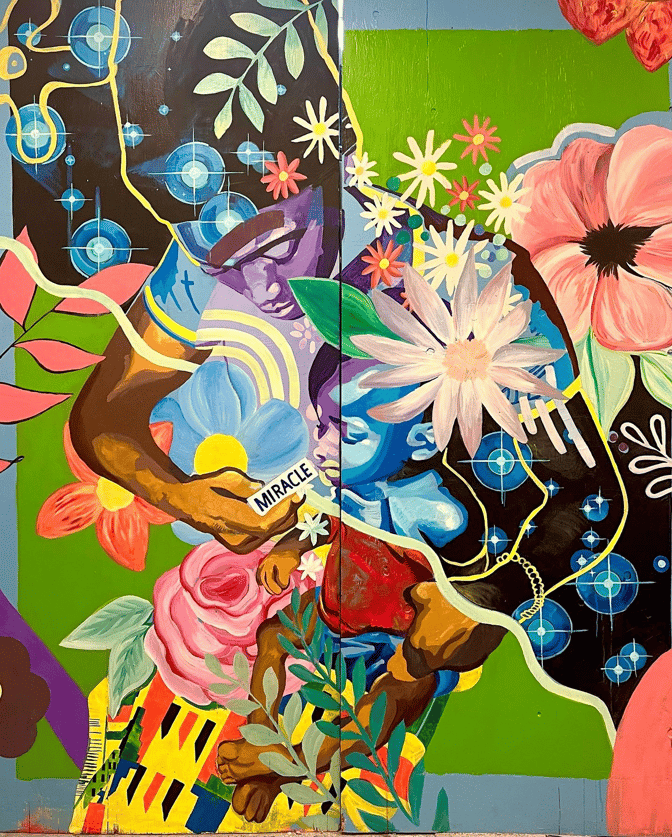

JW: I teach high school art in addition to being an artist. Back here is a piece we're working on - there's an organization called Miracle of Health and they're building a medical center in Sierra Leone. And they commissioned me and encouraged me to make a mural for that hospital. We're celebrating this opportunity. That's a space where you definitely benefit from something encouraging, something uplifting to help you through that time. There are two main areas that are going to be more complex, the [part with a] mother and daughter, and then the [rest] will be more traditional patterns and things like that.

“MIRACLE - As Above, So Below”, 2022. Acrylic on wood. Credit Jesse Wright via Instagram.

BHS: To dive right into it, you were mentioning colors and traditional patterns, and then there's some representation in there as well. Tell me a bit about how you came to work that way, a little intro to your art practice.

JW: That combination is [a way] to speak to what is known and then what is unknown. What is understood and what is not understood. How we traverse through this life and we get glimpses of pieces that we can grasp. I like to establish some kind of balance. So balance of the body, balance of the spirit, balance of the known, balance of the unknown, balance of something representational, to speak to the body and those academic aspects.

But again, just that texture and looseness, creates a nice juxtaposition. A lot of that is seen in urban environments where pieces are fragmented. You might have part of a billboard and then some of that's ripped away. You only get a piece of the message.

We try to understand it as best we can. That's usually how it looks. Half a photo and then white space or brick wall. Some of that is also speaking to this New York City area where you find a lot of those textures, you've got the river and the oceans right there as well. I’m trying to speak to those.

BHS: That makes a lot of sense. I love your thinking about how it's part of a picture you see at moments in time. Because I think sometimes when you're thinking back or looking back, you think you have the whole picture, but you don't. You usually have more fragmented elements.

When people view your work, do you hope that they come out of it understanding that? Is it important that they have a specific message or what do you want your viewers to see?

JW: There are multiple conversations going on. There is the side of, if you're an art maker, you're also partially speaking to those engaged in the dialogue of art making.

And in contributing to that conversation, [you’re] speaking to the history and then bringing something new into it. That's one takeaway. You want that initial aesthetic aspect. The other part is, I've been dealing with intentionally selected images. In the past, I would use found images, make collages and then balance what is known and unknown in speaking to a spiritual journey and then just an everyday experience. I've been looking to the Jamaican side of my family as an allegory for that now. There is a part where the takeaway is documenting these people, their color, their hopes, wishes, and dreams, and their struggles. That's a takeaway, but at the same time, part of that is looking at their story.

A lot of the Jamaican side of my family is returning to Jamaica having gone either to England or America or Canada. And there's that desire to return to their original place. Although it might seem somewhat idiosyncratic, with this Jamaican subject matter the universal takeaway that I'd like to see is a desire to return to an original source of energy, an original place, a homecoming if you will.

And I think that can be universal for anyone transitioning through a situation in life.

BHS: That's really beautiful. I noticed the Jamaican color palette in your works. I love hearing, of course, you explain it and why you're thinking about it in the homecoming. I would imagine that you are depicting different people in different contexts. Your viewers could view and relate to the different people, whether they are the mother in this situation or the child, or what have you. I love that approachability.

JW: Speaking about the colors. I was living in Jersey City and literally billboards would fall from right outside the Holland Tunnel.

I would drag them to my studio and half of the painting would be the billboard. I was choosing imagery that I found and then trying to speak to that narrative of balance. Eventually, I started intentionally choosing images and with the Jamaican colors, I started seeing my family return back to Jamaica, and started looking for the spirit in the family or the spirit in the immediate. I started thinking about, how do we explore family? Because I didn't really do representation work. There were physical aspects or representational aspects because we're bodies, but I was always more interested in the body as an aspect of the narrative, not the final narrative in itself.

So coming to now look at bodies was how to approach that. There's a painting in my family's house of Retrato de Ignacio Sanchez, which is a Diego Rivera piece. And it's just a young boy with a yellow sombrero, but that sombrero also serves kind of like a halo. And he looks like this religious icon in a sense.

Seeing the spirit in the simplicity of everyday was something I got drawn through. A story I share is thinking the human heartbeat is like “boom boom, boom boom”. But my telling of it is that's not the sound of a Jamaican heartbeat. There's a Jamaican song called Ring The Alarm. And the beat's like, mm, mm, mmm, mmm.

I know if you put a stethoscope up to a Jamaican's heart, you're gonna hear that kind of rhythm. It was like that same approach had to be taken with how I approached the figures. So the colors got pushed to be very vibrant. The gesture got more loose. Even though there's some representational aspects, it was like leaving behind some of the traditional approaches to representation and figure.

So that's where those colors and energy came from, I was just trying to put that Jamaican spin on.

Diego Rivera’s “Retrato de Ignacio Sanchez, 1927–1927”. Oil on canvas. Credit Diego Rivera via Artnet.

BHS: You're translating the Jamaican heart into colors and brush strokes. I mean, that's what art is all about. It's supposed to make that connection and that emotion it's supposed to make you feel and relate. Do you have an early childhood memory or do you have a time that you remember from being younger and experiencing art?

JW: Yes, my dad was trying to keep me quiet. He had gone back to college and I was young and he took me into class and to try to stop me from distracting the whole class, he would just doodle old characters, like Mighty Mouse, just whatever he could do quickly.

But to me, that was complete magic. You know, how is this ink turning into these forms of the paper? I think that energy just from watching him do that was very otherworldly and mesmerizing.

Beyond that, I've always had encouraging teachers throughout school who pulled me along and would say if you put some time into this I think you could do this. You could run with this.

I remember when a lot of the galleries were in Soho and just walking in and being confronted with an Anselm Kiefer piece. When you're younger, you see something like Van Gogh and impressionism, you look at its colors and mark making. Anselm Keifer looked like he was putting whole bales of hay and thatch and brick. It's like, how did he get that whole weld and depth onto a two-dimensional piece?

And it broke my jaw. Like he hit me so hard. That was another reinvigoration, when you see something again for the first time and are reminded of what it could be. I'm not saying Anselm Kiefer's my dad, you know, but it's like that moment with my dad again.

Anselm Kiefer’s “Der Gordische Knoten”, 2019. Oil, emulsion, acrylic, shellac, wood and metal on canvas. Credit Anselm Kiefer via White Cube Gallery.

BHS: I love that you have the childhood doodle memory. Anselm Kiefer's also a tricky artist to understand, there's some darkness and there's a lot of heavy emotions in there. It makes you feel something. I feel like that's a wonderful thing about art, even if it doesn't make you feel happy all the time, you're learning a bit more about yourself through it.

JW: I think like you said, that weight it was the same thing. Finding those billboards in Jersey City and New York City, just that weight of the world. So speaking back to some of those formal aspects, that's also an opportunity to add in something delicate right up and juxtaposing those rougher areas, which speaks to the reality of life.

BHS: I love that your work is filled with juxtapositions because I do feel like nothing's straightforward and looking at all different sides at once is important. You found the billboards and incorporated them into your work. It's making me think of spaces and that you're creating such a huge mural as well. Is there anywhere in the world, any location or space that you'd like to create in or have your work displayed in?

JW: That's a good question. Wow. I'm currently under an NDA. I think in a month from now, I could tell you the end is kind of achieved. There's something large on the way.

BHS: So exciting. Well, I won't make you spoil it, but we can look forward to it.

Jesse Wright’s “Three Mothers”, 2020. Credit Jesse Wright via SUNDAYREBEL. Photo by Paul Warchol.

Jesse Wright’s “Three Mothers”, 2020. Credit Jesse Wright via SUNDAYREBEL. Photo by Paul Warchol.

JW: I would say there's three spaces, right? There's the very intimate, the personal, that you share.The excitement of seeing it happen for yourself and your studio and those closest to you. I'm always just grateful to have the opportunity to make art. So the fact that it comes out anywhere is joy.

Then I'm very grateful to live so close to New York City, to be able to go through those galleries. Just walk down a block space after space after space. It’s so generous. It's still free. I'm very grateful for that space and that community, no matter what the price tag is on [the art], you can still walk in and see it and enjoy it.

I have been doing more murals lately and there is something very interesting about that installation size or outstallation size that encompasses that wrapping of space where you can actually change somebody's day, just by virtue of the fact that color is surrounding them. Something different is surrounding them. On some level art just opens you up to thinking that things can be different. So somebody can be going through their day and seeing that, this is a corny example, “I didn't think an apple could look like that.” And then you go, well, maybe the way I'm looking at my life, I could look at it a little bit different, you know? So there's something about those public spaces and murals. Like you were saying with the hospital, just knowing that you can change somebody's environment on that level is another thing I'm grateful to have the opportunity to be a part of.